Ramsgate Beach (Postcode 2217) – Alex Anderson

I’m not sure if they still fall under the definition of ‘polylanguaging’ as the texts are produced by a company, not an individual. However, I think it’s still along the same lines, as it is one entity, choosing to make a choice of language in a specified text.

Caption: L&P Lemonade

Location: Ramsgate Beach Fish & Chip Shop

Date: 25/3/18

Language: English & Maori

Domain: Retail

This is an interesting example of language choice. The use of Maori on the can is somewhat limited, and it is only the name of places. It serves an interesting purpose, as more of a cultural icon, reinforcing the brand’s identity. The use of Maori emphasises the iconic New Zealand product’s origins. Also, the use of the diacritics in the Maori script is an added emphasis, as these generally aren’t used in the signs of the towns they correspond to. I would say the ‘author’ and intended market are both mostly monolingual English speakers, and the Maori is used decoratively, much like how Chinese characters are sometimes used more decoratively than functionally in anglicised Chinese restaurants.

Caption: L&P Lemonade

Location: Ramsgate Beach Coles

Date: 26/3/18

Language: English & Greek

Domain: Retail

I found this interesting pair of contrasting Greek products. To a lot of people, these might both be written off as ‘Greek food & drink’ but their polylanguaging tells the story of two vastly different products. The koulourakia box actually has no Greek script on it at all, even the name of the Greek dessert is written with an English spelling. The soft drink on the other hand, is written entirely in Greek, using the Greek script.

To start, this use of language means that the soft drink is most likely a product made in Greece for Greek consumers, but was imported to Australia. The use of English for the ‘Greek Twists’, on the other hand, suggests that the product was manufactured in Australia, for largely Greek-Australian or Anglo-Australian consumers.

We can also deduce that the intended purpose of the language is different. One could suggest that the Greek on the soft drink is mainly descriptive, and in all purposes related to the consumption and contents of the product. The use of language on the other box is interesting. The name of the brand is written in a font which is reminiscent of the Greek script. This, much like the Maori on the soft drink, gives the brand some identity, and links it to Greece, despite there being no actual Greek-script words on the box. The use of English to write ‘koulourakia’ also links the brand to Greek-Australian consumers, because this is often how they write the word, or at least that’s what I’ve found in my community in Ramsgate Beach.

Caption: Quadrilingual Noodles

Location: Ramsgate Beach Coles

Date: 26/3/18

Language: English, French, Chinese & Japanese

Domain: Retail

Chinese seems to be the predominant language on the box, which isn’t surprising because it says ‘Made in Hong Kong’ at the bottom. It seems to be a mass-produced food product, made for an international market, exported to many different countries. The use of English and French is limited, it just contains the bare minimum that the possible consumer would need: the flavour. Instant noodles are quite common, and most people in the west know how to cook them, so instructions on their preparation aren’t necessary. The use of Japanese is limited to the title, as they are ultimately owned by a Japanese company, and this links the product to its brand.

Lidcombe (Postcode 2141) – Biljana Popovic

The focus this week was to explore the translanguaging in Lidcombe, Sydney, NSW, focusing again on our group’s domain of retail. With reference to translanguaging, the data is centered around language communication, not about the language itself and emphasises the process by which multilingual speakers utilise their languages as an integrated communication system (Garcia, 2009).

Observation 1: Mixed Language Data in Retail (Signage)

Caption: Tip Jar in a Fish Shop

Location: Lidcombe

Date: 26/03/18

Language: English and Spanish

At the Fish shop I noticed that many of the products sold within the shop (alongside the fresh seafood produce) were products of Spanish origin, as I approached the counter I then noticed this tip jar. On the jar itself it includes English and Spanish. This observation is interesting, as the owner of the shop utilised these two languages for the Spanish bilingual or monolingual customer to link these two languages as an integrated system, highlighting the distinct difference between language and communication.

Therefore, the translanguaging on this tip jar sign enables Spanish monolingual and bilingual speakers to make further meaning of the message, thus allowing the receivers to make full flexible use of their bilingual repertoire in a public space (Reid, 2014).

Observation 2: Mixed Language Data in Retail (Product)

Caption: Japanese sheet mask product in cosmetic store

Location: Lidcombe

Date: 25/03/18

Language: Japanese and English

The translanguaging between Japanese and English paints a clear image to the receiver that this sheet mask is of Japanese origin. The translanguaging on the packaging enables both Japanese speakers (monolingual or bilingual) to make sense of the message and thus maximise its communicative potential.

After walking around the store and observing for a little while, I approached the sales assistant and asked about this particular product (since I was interested in purchasing it for myself). The assistant explained to me that she was selectively importing sheet masks that are written not only in (Japanese, Korean e.t.c) but also English, so that domestic individuals better understand how the product works and not have to constantly ask her for help and assistance when purchasing.

Thus, it was interesting to see the intention behind the use of translanguaging from the company to serve a specific target market and their needs. Therefore, this use of translanguaging enables the company to share and communicate the benefits of their product and get this message across with minimal regard to the watchful adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of the Japanese and English languages (Cummins, 2008).

Observation 3: Mixed Language Loose Data Observation at work

Whilst at work, as I am a pharmacy assistant, instead of observing my own languages that I speak to non-English speaking customers in, I casually observed (no recording) the pharmacist in charge speaking Arabic to a regular customer. I was in the dispensary so I was able to overhear his conversation with the woman who came to collect her prescriptions.

Pharmacist in Charge: “lam naraka mundhu muddah, I wondered where you have been” English Equivalent: “Long time no see, I wondered where you have been.” Additionally, when asking about why a medicine went up in price, the woman asked: Woman: “asif! But why is it more expensive?” English Equivalent: “Sorry, But why is it more expensive?”

Location: Lidcombe

Date: 24/03/18

Language: English and Arabic

The conversation between the pharmacist and the female customer was predominantly in English, and the occasional Arabic phrases thrown in, as shown above in the loose transcription. I observed that words with an emotive/personal connotation were spoken in Arabic for e.g. “Sorry” and “Long time no see” signifying that individuals without even recognising themselves move in and out of English to get the message across (Cummins, 2008). Additionally, it should be noted that both of them are fluent speakers of Arabic, but nonetheless are very strong in English and still used it as their main form of communication.

Therefore, this observation demonstrates that individuals actively use resources from different languages together, with very little regard for what we might call the boundaries of named languages such as “English” or “Arabic.” They are using language together to communicate more effectively, and thus are subconsciously accessing different linguistic features or modes to maximise their communicative potential (Garcia, 2009).

Kingsford (Postcode 2032) – Cong Wang

Data for this blog post on translanguaging public signage is based in Kingsford, mainly the Anzac Parade area near UNSW, and my research domain is retail.

I am personally very interested in language contact phenomena of public signs where two or more languages are used, and syntax, morphology or orthography of one language may be affected by the other embedded. Unfortunately, I didn’t find any signage with typical structural or orthographic change, but there is still a relative example.

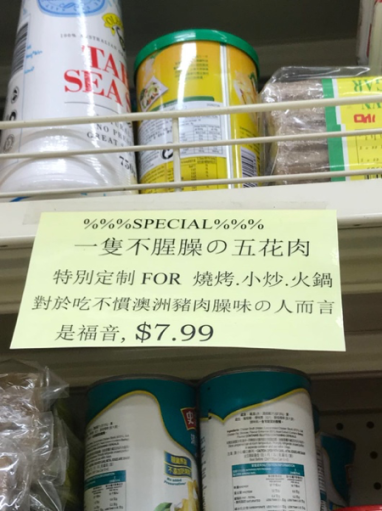

Picture 1

Caption: a price tag in a Chinese retail

Location: Kingsford

Date: 27/03/2018

Language: Traditional Chinese, English, Japanese

Domain: retail/food

‘SPECIAL’ is in English without Chinese translation, but the detailed explanation below of the product, a kind of sauce for cooking meat, is in Chinese only, meaning that this sauce is a perfect choice for those Chinese who don’t like the ‘ gamey smell of Australian meat’, so it actually targets Chinese consumers. Therefore, I think the English ‘SPECIAL’ is used symbolically to attract consumers, and the Chinese explanation is truly what the shopkeeper wants to convey.

What’s more interesting is there are two function words from English and Japanese that are embedded in Chinese, which are ‘for’ and ‘の’ respectively. I think these foreign words are correctly used to substitute the corresponding Chinese function words, without affecting the structure of Chinese. But the shopkeeper didn’t use any content words from English or Japanese, which restresses the point that the expected consumers are Chinese, and to add function words from other languages is just to make it interesting and novel, which is a marketing approach.

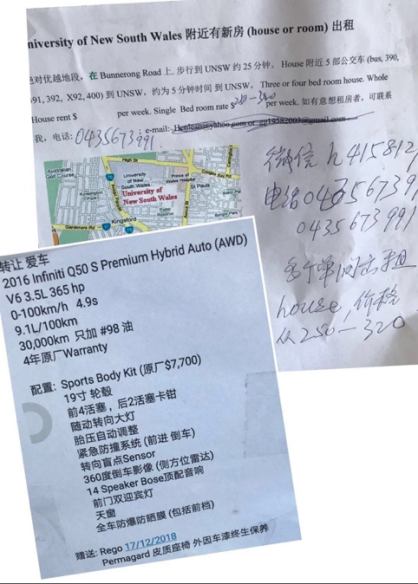

Picture 2

Caption: street ads for car sale and room rent

Location: Kingsford

Date: 27/03/2018

Language: Simplified Chinese, English

Domain: advertisement

The two ads above are basically in Chinese mixed with simple English sentences and words. For instance, in the room rent ad, the author used ‘room’ and ‘house’ in English rather than in Chinese, I think this is to make clear the room to rent is in a house, not in a unit or an apartment. In China, we don’t normally indicate whether it’s a ‘house’, ‘unit’ or ‘apartment’, as most people live in only an apartment, and the rich in maison seem never want to rent their rooms out. So, the author here is trying to follow the customs in Australia to point out what type of accommodation it is.

In the secondhand car ad, the owner used English for some technical words, like ‘Sports Body Kit’ and ‘Sensor’, maybe it’s just hard to find Chinese equivalents for these stuff, for they are more frequently equipped to Australian cars. There’s another English word – ‘warranty’, it says the car has a 4-year warranty. We do have a Chinese equivalent – ‘保修’, but the owner still chose English, I think this is about his/her personal language choice of heteroglossic resources, but from another perspective, we don’t usually have car warranty as long as 4 years in China, which means the Chinese ‘保修’ (warranty)may not be as satisfying as the Australian ‘warranty’, so the owner used English ‘warranty’ to indicate better quality and customer service of this Australian car.

Pagewood (Postcode 2035) – Xue Han

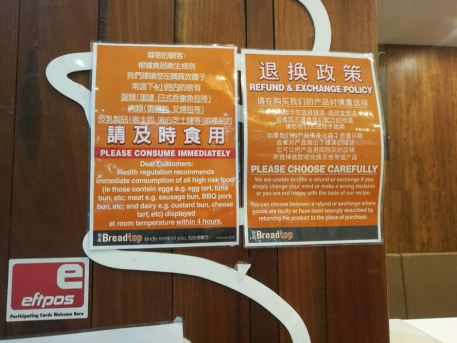

Picture caption: Breadtop

Location: Eastgardens shopping centre

Date: 27/03/2018

Language: English, Mandarin

Domain: Retail

These are two posts in a Chinese bread shop in Eastgardens shopping centre. There are some interesting facts about these posts. On the left-hand side is a post with traditional Chinese and English, saying that breads should be consumed within the day of purchase. However, on the right-hand side, where it says about refund policy, it changes to simplified Chinese. The reason that the shop switches between traditional and simplified Chinese is unknown. But there is a good guess, that is, it intends to cover potential customers using simplified or traditional version of Chinese. In the language community with a large linguistic diversity, shops are using posts to interact with customers with diverse cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, they detailed customers speaking Chinese, and care for those customers by using both simplified and traditional Chinese.

When I observed in the bread shop, I approached to the counter retailer and wanted to see what language she will unconsciously speaks to me. The retail firstly spoke in Chinese (greet: ‘Nihao’, Telling the price “yi gong shi shi san kuai qian), however, when she talks about the bread name (‘Garlic bread’ and ‘croissant’), she switched her language to English. It is interesting that how she uses these two languages in different terms. Daily conversations are made in Chinese, while bread names and technical terms are spoken I English.

Gosford (Postcode 2250) – Jack Waining

In Gosford, it is incredibly difficult to find examples of polylanguaging, however I managed to find a French restaurant in the suburb of Terrigal. The French population of the Central Coast is more concentrated in this area, so it makes sense to have a French restaurant here. The name of the restaurant is written in French, and the description in English. This is possibly to attract the French people to the restaurant as the target audience and also as a measure of authenticity, but the English is included to invite everyone else in.

As seen in the picture, “Le Chat Noir” (The black cat) is written in French, and then “French restaurant” is English.

The same idea can be seen with the menu. Many of the dishes are in French, with the descriptions in English, and certain choices have been made with specific words for different foods. It is clear that French words which have been borrowed into the English language are on display wherever possible, in order to provide as much of a French immersion as possible without disregarding the large English-only population.

Rhodes (Postcode 2138) – Yimiao Xie

As mentioned in my previous posts, Rhodes is a highly multicultural area in Sydney, and the dominant language spoken at home in Rhodes is actually Chinese (Mandarin), hence, this language is highly presented in some retail stores ((ABS, 2016). Just using my personal experience while shopping in New Eastern (the biggest Chinese supermarket in Rhodes), every time when I walked to the counter at the end of the shopping, the cashiers would greed me in English “Hello”, but when I responded with a friendly “Ni Hao (你好)”, they would immediately switch the entire conversation to Mandarin as well. Hence, referring to Horner and Weber (2018), this code-switching could indicate a recognition of our shared language identity, that we are both translanguaging speakers of Mandarin and English, and we have both made agreement to speak with Mandarin. Furthermore, this kind of flexible choice of using languages other than English is quite common in this area, as I could always hear people speaking different languages when I walk around, thus I would say Rhodes is a linguistically diverse suburb.

Photo 1

Caption: A price tag in the Chinese grocery shop. Information in Chinese “Hello, I am white peach. I am cute, please don’t squeeze me, after all I am for eating. Thank you.”

Location: Rhodes

Date: 26/03/18

Language: Chinese, English

Domain: Supermarket

The information contains in this polylanguage sign is quite interesting, as this is not an identical translation between the English words and the Chinese words on this tag. In Chinese, the language employed is much more vivid than its English version of expression, the Chinese part is almost like playing a joke with its customers in a very colloquial way, rather than warning customers not to “squeeze the fruit”, it is more like a dialogue between the “peach” and its consumers. And personally, as a Chinese background speaker I think the language used in this shop is very cute, and it is such a nice way to ask people to be careful while picking fruits. Whereas, the English version is a very straightforward statement, this clearly shows that the shop may have less communicative intention towards those customers who are non-Chinese speakers.

Photo 2

Caption: A price tag written in Chinese and English of a Korean product. Information in Chinese “Special price. Haitai/ Wasabi beef flavor chips.”

Location: Rhodes

Date: 27/03/18

Language: Chinese, English, Korean

Domain: Supermarket

The languages mixing in this photo also reflects the polylanguage environment in retails. However, it seems like Korean is underrepresented on the price tag in this shop, as the product itself is covered by Korean but only Chinese and English are written on the tag. So I would say there is still a limited amount of efforts contributed by the shop owner in promoting polylanguaging. However, in my understanding, this is also understandable as the price tags are offered to its customers who can understand Chinese or English, while the language used on the product package could already serve any Korean speakers.

References

ABS (2016). 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved from http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC13358?opendocument

Horner, K. & Weber, J. (2018). Language and identity. In Introducing Multilingualism (pp.104-123). London: Routledge.

By Alex Anderson, Biljana Popovic, Cong Wang, Xue Han, Jack Waining and Yimiao Xie.